kontrola motora brisaca?

Moderators: pedja089, stojke369, [eDo], trax

kontrola motora brisaca?

ovako,posto radim inkubator trebao bih napraviti mehanizam koji ce mi nakon svakih 5-8h okretat jaja na jednu,pa na drugu stranu,znaci nakon 8h u lijevo ,pa nakon 8h u desno...volio bih da mogu podesavati vrijeme okretanja...pa ako tko ima kakvu ideju,naravno ako mozda postoji i drugacije rjesenje sto se motora tice?hvala

Re: kontrola motora brisaca?

Kolega znam da nisam puno pomogao no sto znaci ovu u citatu nakon 8 h koliko ja znam h znaci sat prema engleskom hour! Jel to mislis na svaki 8 sekundi?komer wrote:znaci nakon 8h u lijevo

Pozz!

znaci,ukljucim motor i okrece se naprimjer udesno i u desno stoji 6-8sati,nakon isteka 6-8 sati pomice se ulijevo,pa stoji u lijevom polozaju 6-8 sati,ovisno o zeljenom vremenu okretanja.....znaci meni treba da se svakih nekoliko sati,ovisno od moje zelje okrece motor u lijevo pa u desno...bez da se moram brinut......

nisam napomenuo da ako jaja stoje pod 90°C,znaci okrecu se 45°C u desno,onda im treba da dodu u lijevo 90°C,znaci pocetni polozaj je 90°C.makar nemora biti,ali nadam se da kuzite,ako ne ,mogu nacrtati!

nisam napomenuo da ako jaja stoje pod 90°C,znaci okrecu se 45°C u desno,onda im treba da dodu u lijevo 90°C,znaci pocetni polozaj je 90°C.makar nemora biti,ali nadam se da kuzite,ako ne ,mogu nacrtati!

Last edited by komer on 21-01-2008, 18:30, edited 1 time in total.

Ja bi to uradio na sledeci nacin:

-Koristio bih motor od brisaca (za automobile zato sto je na 12v)

-Brisaci imaju 2 brzine tako da mozes da biras a i ako ti je prebrzo mozes usporiti zupcanicima i lancem od neke bicikle to bar nije tesko da se uradi ili mozes da napravis regulator pa da podesavas brzinu tako sto regulises jacinu struje na motor.

-Tajmer napravis sa nekim PIC-om toga barem ima na netu koliko hoces i naravno da ide preko releja.

Daj samo nacrtaj kako si zamislio da jaja stoje unutra.

P.S. Motor i tajmer bi stajali sa spoljne strane masine samo bi osovina ulazila u masinu i na osovinu ti idu drzaci za jaja ili sta vec.

-Koristio bih motor od brisaca (za automobile zato sto je na 12v)

-Brisaci imaju 2 brzine tako da mozes da biras a i ako ti je prebrzo mozes usporiti zupcanicima i lancem od neke bicikle to bar nije tesko da se uradi ili mozes da napravis regulator pa da podesavas brzinu tako sto regulises jacinu struje na motor.

-Tajmer napravis sa nekim PIC-om toga barem ima na netu koliko hoces i naravno da ide preko releja.

Daj samo nacrtaj kako si zamislio da jaja stoje unutra.

P.S. Motor i tajmer bi stajali sa spoljne strane masine samo bi osovina ulazila u masinu i na osovinu ti idu drzaci za jaja ili sta vec.

Richard Compton

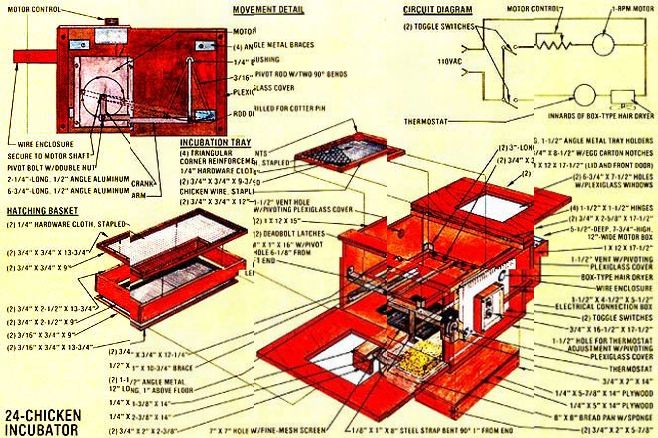

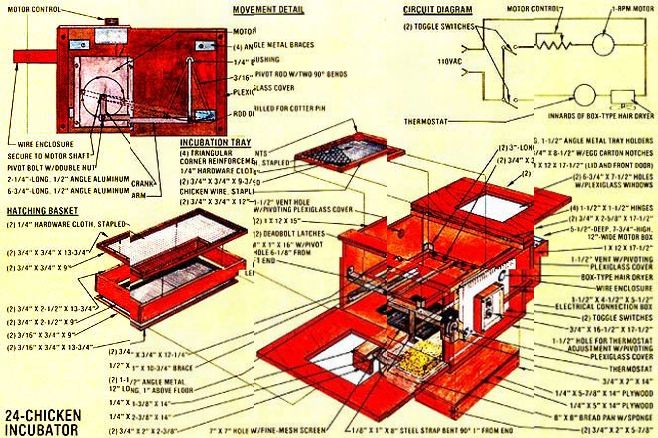

Most folks who keep small flocks of fowl (whether for eggs or meat or both) likely have—at one time or another—considered buying an incubator. The freedom that the devices offer (in maintaining a controlled breeding program and in exchanging less productive hens for better layers) can be a real boon to a farmstead bird operation. Unfortunately, you can purchase quite a few commercially hatched day-old chicks for the price of one quality incubator ... since a store bought apparatus can run from about $150 up (and I mean way up!).

Now it's true that an effective homestead hatchery has to be able to accomplish several jobs at the same time, and that it must do some of them very accurately, but don't let those concerns discourage you from building your own incubator. Once you match the necessary tasks with the various mechanical systems that can handle the chores, the contraption will begin to seem a whole lot less intimidating.

TEMPERATURE

In order to hatch a good percentage of fertile eggs, an incubator must be able to maintain a constant temperature. Though different sorts of eggs require different heat levels, most will grow and hatch well at 99 to 101°F. When incubating chickens and quail, I aim for a steady 99-3/4 °F . . . though the actual temperature may well fluctuate by as much as half a degree. Sure, that does sound imposingly precise, but such accuracy isn't all that difficult to achieve.

The incubator shown in the photos is heated by an old box-type hair dryer (not the fancy new gun variety), which is—in turn—controlled by a thermostat that I purchased from Sears, Roebuck and Co. (ask for Farm and Ranch Catalog No. 32AF88022), for $7.99. Unless the air around the dryer is very warm (it is, after all, designed to work at room temperature), the "high" setting works out fine.

close Close

Is finding the right bolt driving you nuts?

Find just the right fastener for the job in Bolts, Screws and More - A Reference, a handy two-page chart with descriptions and uses of the most common screws, bolts, nuts, washers and anchors. This illustrated reference is fr*e when you subscribe to our fr*e e-newsletter, Mother Earth Living.

Mother Earth Living brings you timely information and expert advice on green living twice a week. Your bonus gift, Bolts, Screws and More - A Reference, is yours fr*e and available instantly when you subscribe.

We will NEVER share your e-mail address with anyone.

Because even 1°F of inaccuracy in a thermometer could make a vital difference in the percentage of the hatch, it's a good idea to use three or four of the instruments and to average their readings. One quarter turn on the thermostat adjustment screw will produce about a 1°F change inside the incubator, so it is possible to home in pretty close to the right level of warmth. (Of course, you'll want to experiment a bit with the various controls before trying the heating system out on your first batch of eggs.)

HUMIDITY

If it's either too dry or too humid inside the incubator, the chicks will suffer. The humidity, measured with a wet-bulb thermometer, will ideally start at 85°F and then rise toward 90°F during the last few days of the incubation period. Low air moisture levels can cause the chicks to stick to their shells, and excessive dampness sometimes produces swelling. (It's important to remember that eggs are permeable and that water, and other substances as well, can get into the shell.)

A sponge, sitting in an 8" X 8" bread pan filled with water, adds moisture to the incubator. Of course, the dimensions of the sponge will depend on just what the relative humidity is to start with, and you'll be able to get it right only after a bit of experimentation. I've found that a 1-1/2"-thick, 4" X 8" sponge suits both extremes of our western North Carolina climate . . . which is typically humid in the summer and relatively dry in the winter. Again, try out different sponges and keep careful track of humidity variation on the hygrometer (remember to use a wet-bulb thermometer with light cloth ... such as Sears Farm and Ranch Catalog No. 32AF88025, which sells for $4.69).

Also, be sure to coat the inside and outside of all the wooden parts of the incubator with a plasticized sealer to hold in the humidity. I used a product called Plasticote, which has worked quite well.

MOVEMENT

The final major requirement for successful incubation is regular movement of the eggs. Studies have shown that a sitting hen will shift her charges an average of 96 times per day. Of course, that frequency can be reduced quite a bit without significantly affecting the hatch, but at least three movements per day are mandatory.

It's possible to get along without a mechanical egg-shifting system, but I've found that holding a steady job prevents me from turning the eggs frequently enough by hand. To solve the problem, I incorporated an automatic system into my mini-hatchery ... and the setup comes highly recommended by this backyard bird breeder!

The eggs in the incubator need to be shifted slowly and smoothly, since jostling would disturb the development of the chicks. I decided to power my system with a Dayton 1-RPM gear motor, coupled to a Dayton solid-state AC-DC and series DC motor control . . . a combination which cuts the oscillation down to about one movement every 45 seconds. [EDITOR'S NOTE: The foregoing items may be available locally. If not, they can be ordered — by a hardware store — from Granger's (the company is a wholesale-only outlet and thus requires a business identification) by requesting Catalog Nos. 3M095 ($13.84) and 4X796 ($12.40), respectively.]The motor is linked to the egg basket by a bent length of 3/8" rod and some angle aluminum ... which form a crank that tilts the assembly approximately 40° in each direction.

TEN INCUBATOR TIPS FOR THE NEWCOMER

[1] Feed your laying hens a good balanced diet, and select only eggs from the best hens.

[2] Pick eggs with good shape and average size. Those that are either too large or too small don't seem to hatch as well.

[3] Never keep the eggs for more than ten days before incubating ... the less waiting, the better. And store them—until you're ready to start the hatching process—at 45 to 60 °F, with plenty of humidity.

[4] Keep the shells clean (but don't wash them). Write on them (to mark dates, etc.) only with soft pencil, and scrub your hands before picking them up.

[5] Preheat the incubator, and let the eggs slowly warm to room temperature before putting them into the hatchery.

[6] Make sure there's enough water in the humidity pan, adding only lukewarm liquid. Cold water could chill the incubator.

[7] Put chicken eggs in trimmed egg containers . . . quail eggs fit nicely in the chicken-wire screen. (The big end always goes up.)

[8] Move quail eggs to the lower rack on the 14th day . . . chickens should be shifted down on the 19th. Don't open the incubator after that point until the hatch is complete.

[9] Leave the brand-new chicks in the incubator for 24 hours . . . or until they dry. (Be sure the screened cover is in place, or they could jump out and drown in the water pan.)

[10] Clean the incubator thoroughly, after each hatching, with a dilute solution of chlorine bleach. And remember to rinse it well, too!

EGGSTACY

The apparatus shown in the photos and drawings will hold two dozen chicken (or 60 quail) eggs. Of course, it could be built larger or smaller, but if you opt for greater capacity, I'd suggest that you make the device wider rather than try to add another level.

So far I've been able to hatch about 65% of all the fertile quail eggs that I can get (with the exception of one run that was ruined by a power failure). Chicken hatch rates should be a little higher than that . . . perhaps into the 70% range. The local extension agent tells me that those percentages are as good as could be expected from a small commercial incubator, so I think the $60 I invested was money well spent!

Most folks who keep small flocks of fowl (whether for eggs or meat or both) likely have—at one time or another—considered buying an incubator. The freedom that the devices offer (in maintaining a controlled breeding program and in exchanging less productive hens for better layers) can be a real boon to a farmstead bird operation. Unfortunately, you can purchase quite a few commercially hatched day-old chicks for the price of one quality incubator ... since a store bought apparatus can run from about $150 up (and I mean way up!).

Now it's true that an effective homestead hatchery has to be able to accomplish several jobs at the same time, and that it must do some of them very accurately, but don't let those concerns discourage you from building your own incubator. Once you match the necessary tasks with the various mechanical systems that can handle the chores, the contraption will begin to seem a whole lot less intimidating.

TEMPERATURE

In order to hatch a good percentage of fertile eggs, an incubator must be able to maintain a constant temperature. Though different sorts of eggs require different heat levels, most will grow and hatch well at 99 to 101°F. When incubating chickens and quail, I aim for a steady 99-3/4 °F . . . though the actual temperature may well fluctuate by as much as half a degree. Sure, that does sound imposingly precise, but such accuracy isn't all that difficult to achieve.

The incubator shown in the photos is heated by an old box-type hair dryer (not the fancy new gun variety), which is—in turn—controlled by a thermostat that I purchased from Sears, Roebuck and Co. (ask for Farm and Ranch Catalog No. 32AF88022), for $7.99. Unless the air around the dryer is very warm (it is, after all, designed to work at room temperature), the "high" setting works out fine.

close Close

Is finding the right bolt driving you nuts?

Find just the right fastener for the job in Bolts, Screws and More - A Reference, a handy two-page chart with descriptions and uses of the most common screws, bolts, nuts, washers and anchors. This illustrated reference is fr*e when you subscribe to our fr*e e-newsletter, Mother Earth Living.

Mother Earth Living brings you timely information and expert advice on green living twice a week. Your bonus gift, Bolts, Screws and More - A Reference, is yours fr*e and available instantly when you subscribe.

We will NEVER share your e-mail address with anyone.

Because even 1°F of inaccuracy in a thermometer could make a vital difference in the percentage of the hatch, it's a good idea to use three or four of the instruments and to average their readings. One quarter turn on the thermostat adjustment screw will produce about a 1°F change inside the incubator, so it is possible to home in pretty close to the right level of warmth. (Of course, you'll want to experiment a bit with the various controls before trying the heating system out on your first batch of eggs.)

HUMIDITY

If it's either too dry or too humid inside the incubator, the chicks will suffer. The humidity, measured with a wet-bulb thermometer, will ideally start at 85°F and then rise toward 90°F during the last few days of the incubation period. Low air moisture levels can cause the chicks to stick to their shells, and excessive dampness sometimes produces swelling. (It's important to remember that eggs are permeable and that water, and other substances as well, can get into the shell.)

A sponge, sitting in an 8" X 8" bread pan filled with water, adds moisture to the incubator. Of course, the dimensions of the sponge will depend on just what the relative humidity is to start with, and you'll be able to get it right only after a bit of experimentation. I've found that a 1-1/2"-thick, 4" X 8" sponge suits both extremes of our western North Carolina climate . . . which is typically humid in the summer and relatively dry in the winter. Again, try out different sponges and keep careful track of humidity variation on the hygrometer (remember to use a wet-bulb thermometer with light cloth ... such as Sears Farm and Ranch Catalog No. 32AF88025, which sells for $4.69).

Also, be sure to coat the inside and outside of all the wooden parts of the incubator with a plasticized sealer to hold in the humidity. I used a product called Plasticote, which has worked quite well.

MOVEMENT

The final major requirement for successful incubation is regular movement of the eggs. Studies have shown that a sitting hen will shift her charges an average of 96 times per day. Of course, that frequency can be reduced quite a bit without significantly affecting the hatch, but at least three movements per day are mandatory.

It's possible to get along without a mechanical egg-shifting system, but I've found that holding a steady job prevents me from turning the eggs frequently enough by hand. To solve the problem, I incorporated an automatic system into my mini-hatchery ... and the setup comes highly recommended by this backyard bird breeder!

The eggs in the incubator need to be shifted slowly and smoothly, since jostling would disturb the development of the chicks. I decided to power my system with a Dayton 1-RPM gear motor, coupled to a Dayton solid-state AC-DC and series DC motor control . . . a combination which cuts the oscillation down to about one movement every 45 seconds. [EDITOR'S NOTE: The foregoing items may be available locally. If not, they can be ordered — by a hardware store — from Granger's (the company is a wholesale-only outlet and thus requires a business identification) by requesting Catalog Nos. 3M095 ($13.84) and 4X796 ($12.40), respectively.]The motor is linked to the egg basket by a bent length of 3/8" rod and some angle aluminum ... which form a crank that tilts the assembly approximately 40° in each direction.

TEN INCUBATOR TIPS FOR THE NEWCOMER

[1] Feed your laying hens a good balanced diet, and select only eggs from the best hens.

[2] Pick eggs with good shape and average size. Those that are either too large or too small don't seem to hatch as well.

[3] Never keep the eggs for more than ten days before incubating ... the less waiting, the better. And store them—until you're ready to start the hatching process—at 45 to 60 °F, with plenty of humidity.

[4] Keep the shells clean (but don't wash them). Write on them (to mark dates, etc.) only with soft pencil, and scrub your hands before picking them up.

[5] Preheat the incubator, and let the eggs slowly warm to room temperature before putting them into the hatchery.

[6] Make sure there's enough water in the humidity pan, adding only lukewarm liquid. Cold water could chill the incubator.

[7] Put chicken eggs in trimmed egg containers . . . quail eggs fit nicely in the chicken-wire screen. (The big end always goes up.)

[8] Move quail eggs to the lower rack on the 14th day . . . chickens should be shifted down on the 19th. Don't open the incubator after that point until the hatch is complete.

[9] Leave the brand-new chicks in the incubator for 24 hours . . . or until they dry. (Be sure the screened cover is in place, or they could jump out and drown in the water pan.)

[10] Clean the incubator thoroughly, after each hatching, with a dilute solution of chlorine bleach. And remember to rinse it well, too!

EGGSTACY

The apparatus shown in the photos and drawings will hold two dozen chicken (or 60 quail) eggs. Of course, it could be built larger or smaller, but if you opt for greater capacity, I'd suggest that you make the device wider rather than try to add another level.

So far I've been able to hatch about 65% of all the fertile quail eggs that I can get (with the exception of one run that was ruined by a power failure). Chicken hatch rates should be a little higher than that . . . perhaps into the 70% range. The local extension agent tells me that those percentages are as good as could be expected from a small commercial incubator, so I think the $60 I invested was money well spent!

Last edited by stojke369 on 21-01-2008, 19:34, edited 1 time in total.

znaci,

http://img260.imageshack.us/my.php?imag ... 005hq2.jpg

na ovoj slici su jaja okrenuta za 45°ulijevo,i tako budu 6-8 do do okretanja u desno u polozaj od 45°...nadam se da je jasnije!

http://img260.imageshack.us/my.php?imag ... 005hq2.jpg

na ovoj slici su jaja okrenuta za 45°ulijevo,i tako budu 6-8 do do okretanja u desno u polozaj od 45°...nadam se da je jasnije!

Tako sam i mislio na osovini je unutrakomer wrote:znaci,

http://img260.imageshack.us/my.php?imag ... 005hq2.jpg

na ovoj slici su jaja okrenuta za 45°ulijevo,i tako budu 6-8 do do okretanja u desno u polozaj od 45°...nadam se da je jasnije!

Samo tu osovinu produzi napolje.Na kraj osovine navari zupcanik od bicikle pa preko lanca na motor koji takodje ima zupcanik zavisno od velicine zupcanika podesavas brzinu okretanja mada brzinu kao sto sam i rekao mozes da regulises strujom na motor.

@djura 012 je upravu tajmer resi ovim ima ga u svakoj prodavnici elektrotehnicke robe i nije skup imas ih digitalnih kao sa slike i mehanickih.

Krajnji polozaj odredis mikro prekidacima kao sto je isto @djura 012 rekao da nebi preteralo mada i mebi trebalo da pretera zato sto je motor od brisaca.Znaci kada mikro prekidac za jedan i drudi polozaj kada se naprimer aktivira jedan prekidac on prekida struju za taj smer i moze jedino da krene u drugi smer.

Krajnji polozaj odredis mikro prekidacima kao sto je isto @djura 012 rekao da nebi preteralo mada i mebi trebalo da pretera zato sto je motor od brisaca.Znaci kada mikro prekidac za jedan i drudi polozaj kada se naprimer aktivira jedan prekidac on prekida struju za taj smer i moze jedino da krene u drugi smer.